FACE-TO-FACE AND SOCIALLY DISTANT (2020)

Texts

*written in lockdown #1 in 2020 in London:

FACE-TO-FACE AND SOCIALLY DISTANT:

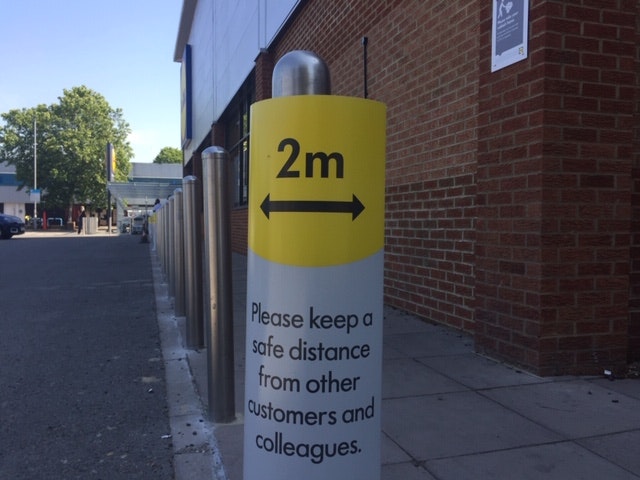

In this world marked by its distance rule of 2m, m2 gallery offers a face-to-face exhibition.

Image: Carolin Meyer

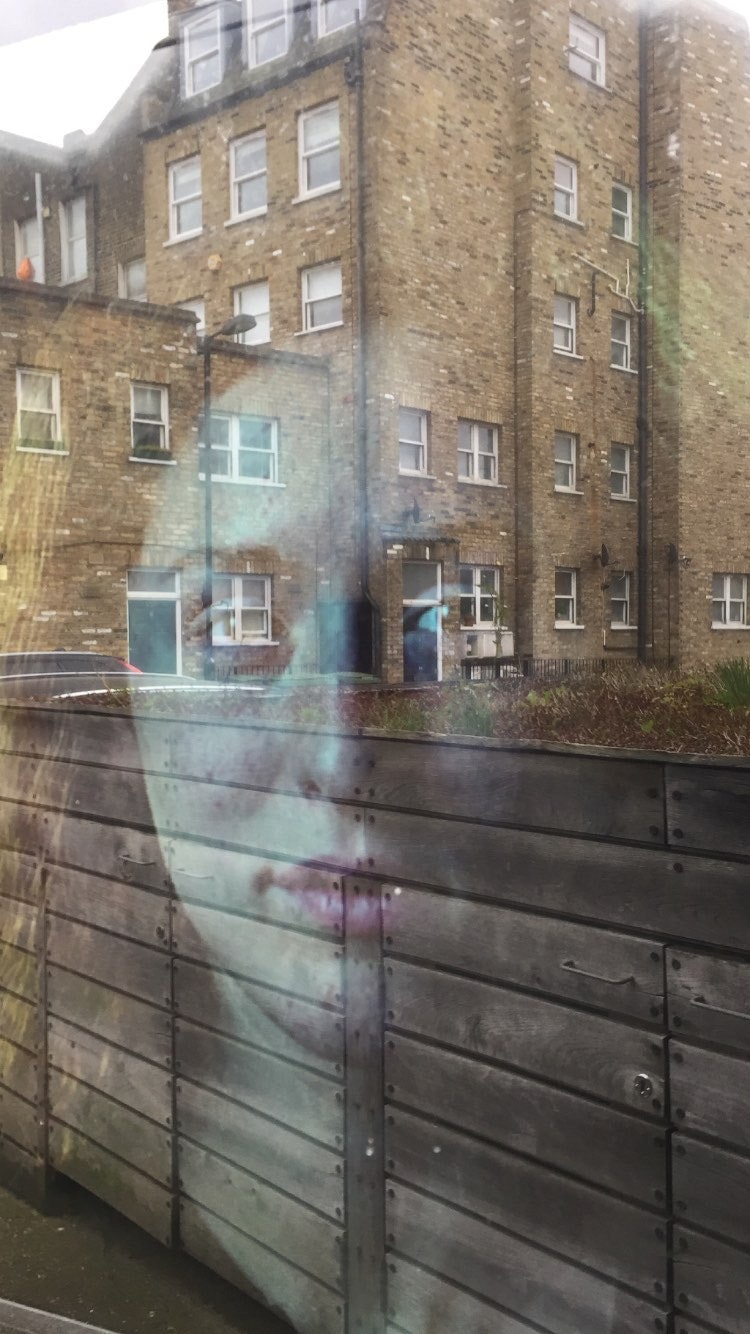

When I was venturing out for my “essential” shopping in week five of Lockdown in South East London, I made a discovery worth sharing. It is especially worth sharing for those who miss going to galleries or those who want to spice up their lockdown schedules with something new: an exhibition that can be fully experienced despite of Coronavirus. At 2c Kings Grove, just by Queens Road Peckham station, m2 gallery is “giving back to the street” by exhibiting art in their one metre square by half a metre-deep window gallery. The not-for-profit space has been run and curated by artist/curator/architect Ken Taylor and artist/curator Julia Manheim since 2003. m2’s current exhibition, "Pause", is showing moving-image portraits by the artist Gerry McCulloch, which can be visited 24 hours a day, every day, by anyone who comes past and wants to have a closer look.

Image: m2 gallery.

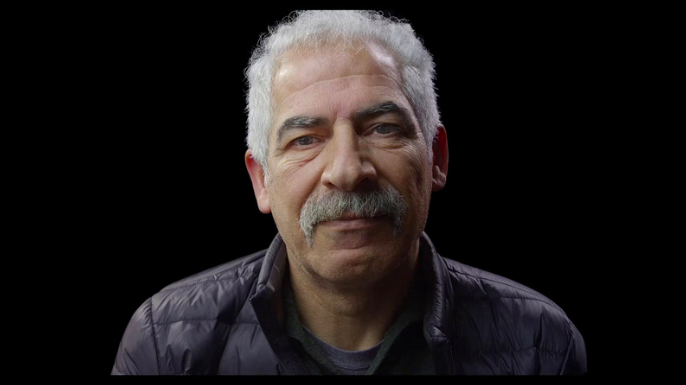

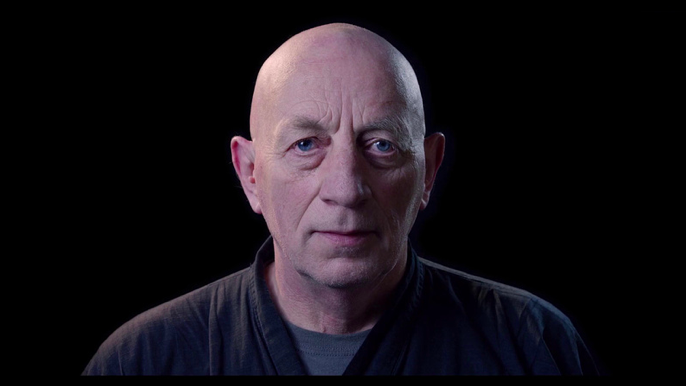

The exhibition consists of five screens, with each screen showing a different close-up of a person’s face. Three of the five screens can already be spotted from the street when passing by, the other two can be found when walking over the pavement and around the wooden construction that houses m2 gallery. The various people’s faces, captured by the artist, are looking back at the camera - silently and only with little movement. Their public display, approachable from the pavement, and the screen’s instalment at eye level, mean that anyone who finds themselves in front of them, can enter into a face-to-face conversation without words with the person on the screen. After some time, a new face will appear, and another face-to-face encounter is made possible. The exhibition text located by the fifth screen, behind the wooden gallery construction, states that, these moving-image portraits engage participants “deeply but silently with each other”.

In these times of social distancing, seeing another person’s face in an in-person encounter can be dramatically sparse, especially when living and isolating alone. The government-ensued rules of staying inside are to keep people physically apart from one another to prevent the further spread of Covid-19. Therefore, public spaces have practically been rendered empty, all public events are cancelled, and people outside their own households are, simply, not allowed to meet.

However, a lot of people are recognising that their lifestyles have not changed much since lockdown. They are realising that they have been living their lives mainly indoors and socially isolated before. Various memes of before and during lockdown, show a person on their laptop indoors. Online artist residencies, such as @self_isolation_residency on Instagram, have posted hard-hitting statements such as: Think of all the ways we were already socially distant. Others have joked that they didn’t know their lifestyles were called self-isolation. Numerous articles are trying to grasp the reach of the current pandemic and its implications on our lifestyles. In particular, something that the columnist Waleed Aly wrote in an article on The Sydney Morning Herald website, stayed with me: “Pandemics don’t change us, at least in the short term. They reveal us. We come to them as we’ve been formed over decades, and we respond accordingly.” So, what does the pandemic reveal about us? How do we come to this pandemic? And what has formed us over the decades and makes us respond accordingly?

Didn't we come to this pandemic as already socially distant to each other? Hasn't this pandemic revealed that many of us were living in social isolation all along? Weren't face-to-face encounters and unmediated social interaction rare before lockdown?

What is it that has formed us over the past decades to cause this previous collective feeling of isolation that has now been so painfully revealed by the Covid-19 pandemic?

One thing that has undoubtedly formed us, after we have formed it, is the internet with its promise to connect us all in a “world wide web”. Technically, we are available at any time, anywhere, and to anyone via mobile phone, “social” media and email. In reality, this constant availability leads to an exhaustion of the social, where the lines between social, intimacy and work have long become blurred. Being social now equates with being connected and being connected is a given. We are expected to be always-on and always-available – equally for our family, friends, colleagues, bosses and everyone else, via the same internet technologies. The MIT professor Sherry Turkle calls this the freeing-enslaving paradox - a paradox in which the smartphone allows us the freedom to communicate with others, to be entertained, to work remotely, and to access information from anywhere, but one that dictates that we must always be on and constantly available. This brings with it a sense of responsibility, or even obligation, to respond in a timely fashion to the technology. I think it's time we admit that we got stuck in the web. We started with the illusion that technology will give us control and ended up as the controlled. We got smartphones to manage our emails but find ourselves cradling our phones in bed first thing in the morning and last thing at night. We have allowed technology to shape our emotional lives, where it defines and redefines our perceptions of sociability, self, intimacy and privacy. In what other ways technology has changed our relationships becomes clear when looking at another paradox, Turkle writes about in her book, Alone Together: Why we expect more from Technology and less from Each Other (2011). Testifying for the loss of in-person face-to-face encounters, the present-absent paradox describes how we are physically present for those around us, but are really absent, preoccupied with our smartphones. The paradox arises in the fact that we need solitude in order to connect, or we need to temporarily neglect those physically around us to offer our attention to those absent. Turkle notes that, “being alone can start to seem like a precondition for being together because it is easier to communicate if you can focus, without interruption, on your screen.” The present-absent paradox is one way in which we were already socially distant. Think of the way playing a video game, for instance, requires us to be alone with our screen. Think of the way watching television requires us to at least be indoors. Think of the way going online, to connect with others on social media, requires us to be alone with our smartphone or laptop. Another phenomenon that makes people fall back on mediated interaction over in-person interaction is “phubbing”. “Phubbing” is a combination of the words “phone” and “snubbing”, and, to be phubbed is “to be snubbed by someone using their phone when in each other's company”. As the researchers, Meredith E. David and James A. Roberts, state in their study, My life has become a major distraction from my cell phone: Partner phubbing and relationship satisfaction among romantic partners (2016), the omnipresent nature of the smartphone makes phubbing an inevitable occurrence. They further found that phubbed individuals experience a sense of social exclusion, which leads to a heightened need for attention and results in individuals attaching to social media in hopes of regaining a sense of inclusion. They conclude that although the purpose of technology like smartphones is to help us connect with others, in this particular instance, it does not.

The ways in which we were already socially distant, consequently, are the ways we use to entertain or distract ourselves, connect with each other and work. These all happen online and via a screen. They demand us to be alone or at least fixated on the screen. And when one of us is fixated on the screen, the other is more likely to get out their smartphone, too, to overcome the feeling of exclusion when being phubbed. Turkle suggests in her book, Reclaiming Conversation (2015), that increased engagement with technology may lead people to immerse themselves in idealised online identities that help them avoid those in-person and in-depth conversations, in which we allow ourselves to be fully present and vulnerable - in other words, those conversations, where empathy and intimacy flourish. What else might we lose if we lose the ability to 'do' empathy and intimacy face-to-face?

Image: US Fisher Price

Teenagers or "digital natives" are among the groups that was spending most of their time already on their phones and that before the pandemic. They socialise via their phones. They don’t need to leave their homes to spend time with their friends. “I’ve been on my phone more than I’ve been with actual people. […] My bed has, like, an imprint of my body.” This statement is from a 13-year-old girl and was shared by the psychologist Jean Twenge from her research about generational differences in the US in an article on the website of The Atlantic in 2017. In the article, Twenge also mentions a national survey on happiness in teenagers, which showed that today “all screen activities are linked to less happiness, and all non-screen activities are linked to more happiness. […] But those who spend six to nine hours a week on social media are still 47 percent more likely to say they are unhappy than those who use social media even less. The opposite is true of in-person interactions. Those who spend an above-average amount of time with their friends in person are 20 percent less likely to say they’re unhappy than those who are with their friends for a below-average amount of time.” Turkle stresses how hard it was for today’s youth to learn social and emotional skills with hyperconnectivity getting in the way with stillness and time to discover their feelings. She says, “today’s adolescents have no less need than those of previous generations to emphatic skills, to think about their values and identity, and to manage and express feelings. They need time to discover themselves, time to think. But technology, put in the service of always-on communication and telegraphic speed and brevity, has changed the rules of engagement with all of this. When is downtime, when is stillness? The text-driven world of rapid response does not make self-reflection impossible, but it does little to cultivate it.”

Covid-19 has slowed the world down. Businesses are shut, most work is cancelled, public transports have come to a halt. The ever-spurting engine of capitalism has stopped and arguably remains silent for the unforeseeable future. For those privileged enough to be furloughed from their work, this is a break like never before - a break from the constant pressure to be productive, from working as many shifts as possible to be able to pay the bills, and from being in constant demand to perform well and ensure to be kept on after their 6-months-employment-contracts end. This situation is so unusual that most people are not even expected to be available via phone, social media or email anymore. On the contrary, there is a mutual understanding that this is a vulnerable time, because of the general uncertainty in all areas of life, brought on by the unknown new virus. People are acknowledging that they are all "in the same boat", or, more truthfully, in the same storm, in different boats of different sizes and with different levels of comfort and discomfort, but, nevertheless, in the same storm.

Downtime is now, stillness is now – now, in this pandemic. [At least, as we've come to realise in hindsight; for the first few weeks.]

Now, that many of us are released from the pressure to be always on and productive, there is time for self-reflection and thinking about what makes each of us individually happy and what makes us unhappy, what we were lacking before the pandemic and what changes we need to make for our well-being 'after' the pandemic. Now, that we are deprived of human contact, of meeting face-to-face, of seeing our family, of being immersed in a group, we are realising what we are missing. In this time of physical distancing, we are absolutely dependant on technology to connect with others and have no other choice than to substitute seeing loved ones in real life with seeing them on our screens. It is in this state of obligated separation, that we might realise that what we are lacking most of all is human contact.

We will crave "experiences that are haptic, shared and void of digital mediation", says Franco "Bifo" Berardi in an interview in 2020, going further and stating that people will identify online connectivity with sickness. In support of the attempt to relearn the intimacy of face-to-face encounters, I return to "Pause" - the exhibition at m2 gallery, inviting us to take a break from our isolated lifestyles - the exhibition that can be visited despite the closures ensued by the pandemic.

"Pause" opened just before the pandemic hit London on March 8, 2020. By coincidence, the moving-image portraits are exhibited in a time, where human contact is as sparse as ever due to social distancing and self-isolation rules. Of course, there is no actual returning gaze when looking at the people’s faces. However, with these moving-image portraits the artist elicits face-to-face encounters which convey a sense of social intimacy, which can only be experienced in relation to another person looking at one. The reverberations that these encounters have, give way to nostalgia and longing for social encounters in real life. In his artist statement, Gerry McCulloch emphasises the importance of relating to one another:

“Imagine you and I are standing opposite each other. I may silently acknowledge that I am here, and you are there, even although your here is my there and vice-versa. My here exists only in relation to you, and your here exists only in relation to me. There is no inherently existing here or there for either of us. Nevertheless, both of our impressions are accurate in the context of our contrasting perspectives and it would be mistaken for either of us to suppose that our here does not exist at all. While there is little doubt that we each exist as discrete entities; in crucially important respects, I only exist because you exist, and you only exist because I exist.”

In realising and acknowledging that both parties only exist in relation to one another, a sense of empathy, naturally, comes to the surface. It is no wonder that the act of pausing to look at one another is a recognised exercise in empathy. There is something tender and loving in taking the time to really look. However, most of the time, our eyes are glued to the screens in our hands, with our bodies hunched over our devices and our thumbs scrolling through thousands of images of other people; strangers, on our social media sites or on the never-ending news. Sometimes our phones can serve as protection. We don’t want to risk being ignored when we are speaking to someone in person, so when the other person gets their phone out throughout our conversation, getting one's own phone out can convey that we are not bothered by it. However, every time we are phubbed, a little bit of our trust in other people dies, and intimacy is pushed further and further away from our reach.

This pandemic, in which we no longer have the choice, but can only get in contact with one another via our devices, might remind us to consider abandoning our phones when we choose to be in each other’s company again. As Turkle says: “What is a place if those who are physically present have their attention on the absent?” So, if you are thinking of going to m2 in Peckham, you might also consider that this gallery visit would be without the usual exposure to other people, which is, of course, important to prevent further Coronavirus infections. However, one kind of exposure is provided by "Pause", which is the much-needed exposure to another person’s face, making way, for a “conversation without words”.

The artist Ian Alan Paul refers to the pandemic as a “social relation among people, mediated by viruses.” Therefore, meaning, I only exist, because you exist, and, because you are practicing social distancing, and, in turn, you only exist because I exist in relation and with respect to you. At this moment in history, staying apart from one another is a social act. Might this explain, why it’s called social distancing and not physical distancing? The virus has revealed our interdependencies, and we must realise how our actions affect everyone around us. Ultimately, we are dependent on our social relations – face-to-face, on-screen, and, once lockdown is behind us, again in the vulnerable, but indispensable flesh.

-----

"Pause" is on until Friday, 29 May 2020, at m2 gallery at 2c Kings Grove, Peckham, London, SE15 2NB.

T. 44 0207 771 1600

E.info@m2gallery.com

W.http://www.m2gallery.com

If you missed it IRL, you can view Gerry McCulloch’s moving-image portraits here: https://www.darshanaphotoart.co.uk/transpires.

The next exhibition at m2 gallery, “Car Quarantine?”, consists of photographic conversations by Ken Taylor of cars acquiring gossamer overlays as they take on an enforced redundancy in late lockdown.

https://m2gallery.com/ken-tayl...